3D printing in the medical field:major applications revolutionising the industry- B-AIM PICK SELECTS

- Allie Nawrat

- Sep 16, 2020

- 3 min read

3D printing has many functions in a variety of industries, however, in the medical field it has four main applications. Allie Nawrat found out how this technology could be used to replace human organ transplants, speed up surgical procedures, produce cheaper versions of required surgical tools, and improve the lives of those reliant on prosthetic limbs.

Additive manufacturing, otherwise known as 3D printing, was first developed in the 1980s. It involves taking a digital model or blueprint of the subject that is then printed in successive layers of an appropriate material to create a new version of the subject.

The technique has been applied to (and utilised by) many different industries, including medical technology. Often medical imaging techniques, such as X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and ultrasounds are used to produce the original digital model, which is subsequently fed into the 3D printer.

It has been forecast that 3D printing in the medical field will be worth $3.5bn by 2025, compared to $713.3m in 2016. The industry’s compound annual growth rate is supposed to reach 17.7% between 2017 and 2025.

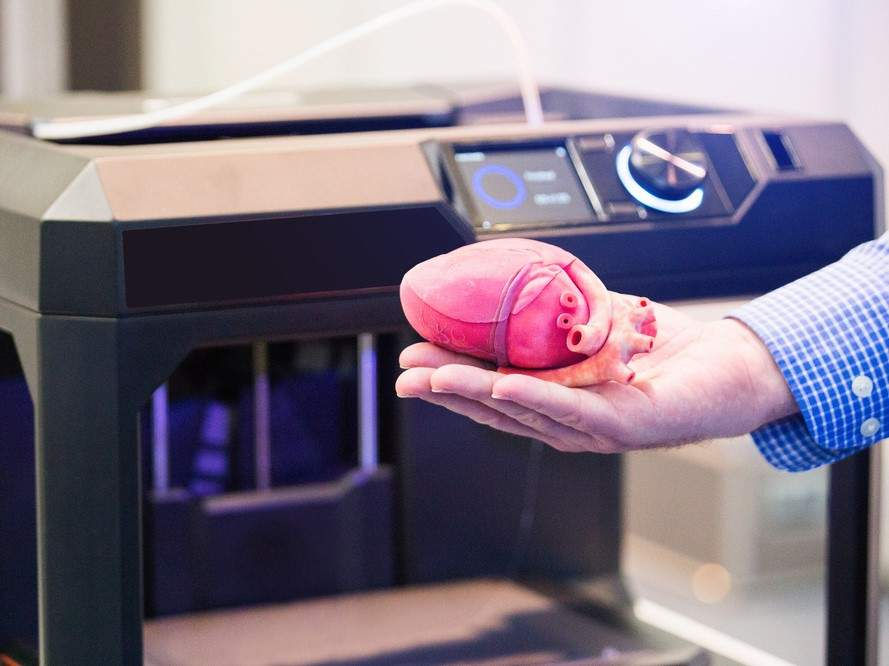

There are four core uses of 3D printing in the medical field that are associated with recent innovations: creating tissues and organoids, surgical tools, patient-specific surgical models and custom-made prosthetics.

Bioprinting tissues and organoids

One of the many types of 3D printing that is used in the medical device field is bioprinting. Rather than printing using plastic or metal, bioprinters use a computer-guided pipette to layer living cells, referred to as bio-ink, on top of one another to create artificial living tissue in a laboratory.

These tissue constructs or organoids can be used for medical research as they mimic organs on a miniature scale. They are also being trialled as cheaper alternatives to human organ transplants.

US-based medical laboratory and research company Organovo is experimenting with printing liver and intestinal tissue to help with the studying of organs in vitro, as well as with drug development for certain diseases. In May 2018, the company presented pre-clinical data for the functionality of its liver tissue in a programme for type 1 tyrosinemia, a condition that impedes the body’s ability to metabolise the amino acid tyrosine due to the deficiency of an enzyme.

The Wake Forest Institute in North Carolina, US, adopted a similar approach by developing a 3D brain organoid with potential applications in drug discovery and disease modelling. The university announced in May 2018 that it’s organoids have a fully cell-based, functional blood brain barrier that mimics normal human anatomy. It has also been working on 3D printing skin grafts that can be applied directly to burn victims.

Surgery preparation assisted by the use of 3D printed models

Another application of 3D printing in the medical field is creating patient-specific organ replicas that surgeons can be use to practice on before performing complicated operations. This technique has been proven to speed up procedures and minimise trauma for patients.

This type of procedure has been performed successfully in surgeries ranging from a full-face transplant to spinal procedures and is beginning to become routine practice.

In Dubai, where hospitals have a mandate to use 3D printing liberally, doctors successfully operated on a patient who had suffered a cerebral aneurysm in four veins, using a 3D printed model of her arteries to map out how to safely navigate the blood vessels.

In January 2018, surgeons in Belfast successfully practiced for a kidney transplant for a 22-year-old woman using a 3D printed model of her donor’s kidney. The transplant was fraught with complications as her father, who was her donor, had an incompatible blood group and his kidney was discovered to have a potentially cancerous cyst. Using the 3D printed replica of his kidney, surgeons were able to assess the size and placement of the tumour and cyst.

Comments